Moving from Cuba to the United States at 10 years old, poet Yosie Crespo found herself losing touch with her native Spanish. American schools pressured her to write “everything in English,” which she felt “was breaking me apart from my country.”

“It was like putting aside what you are, where you came from, what your parents taught you up until then. And so I did, I did what the teachers told me to do,” she said. But, she added, she “never let go” of her native language, by writing in Spanish after finishing her school work in English.

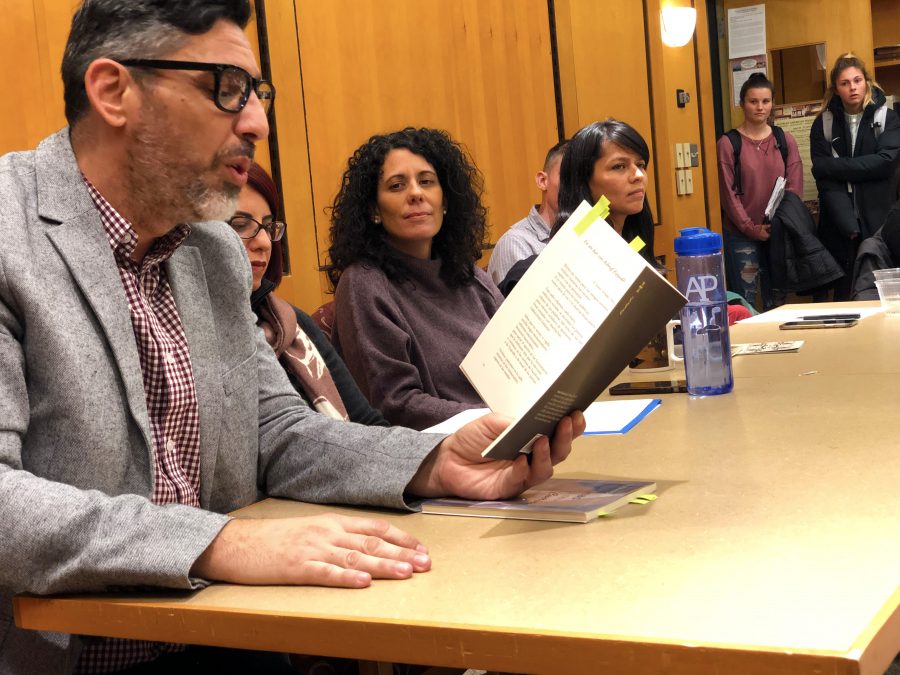

The college’s Foreign Languages and Literatures department hosted Spanish poets Silvia Goldman and Crespo. Along with the writers, Spanish professor Amauri Gutiérrez-Coto and French professor Mathieu Perrot read from their own works, both in Spanish. Each poet read about four poems from their collections.

One of the poems that Crespo read was entitled “Lamento De Àngel Oculto Ante Revelación,” which translates to “The Hidden Lament of an Angel Before Revelation.”

The inspiration for the poem sparked out of frustration with people constantly “trying to be perfect,” Crespo said.

“We live in a very materialistic world, where everything you see is not…what it seems.” The poem urges readers to be “aware” of the deceptions of life, adding that people are not always good, or bad—that there is an “in-between.”

To Crespo, poetry was “always a necessity…I found in my poetry a place to find myself…that was the one thing that helped me to become who I am today.”

During the reading, Crespo mentioned that although she thinks and speaks English, she much prefers to write and read her poems in Spanish.

Her overall inspirations stems from “the simplest things you can imagine,” such as conversations with co-workers, someone she just met, or a word someone happened to say. Those inspirations “haunts” her until she’s able to write them down.

“From a conversation with a co-worker, someone I just met, a word that [someone] just said…” Crespo said. “It could be something you hear and suddenly have a poem in your head…it haunts you into you write it and let it go. If you don’t write it they keep piling up.”

For Goldman, who is from Uruguay, playing with the musicality of her work when read out loud is at the main core of her poetry. She spends time identifying and looking for the rhyme in her poems. “Something about the rhythm or the music of the poem is what takes me. It’s really what rides the poem. Some words are taking away of the poems because it doesn’t fit the incantatory rhythm that I want.”

The magic of poetry, Goldman said, is that it becomes “like a linguistic phenomenon,” and “a linguistic opportunity for something to happen.”

The poems that Goldman read from her collection “De los peces la sed” includes, “Manos de hambre,” “Te miro para descansar,” and the first in the collection, “nocturno del hueco.”

“nocturno del hueco,” was inspired by the Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca, who also has a poem under the same title. Lorca is her overall inspiration. Goldman said that when reading Lorca’s book “Romancero Gitano,” “one would notice a sense of liturgy, like a prayer almost that takes you.”

Additionally, her son played a huge role in “nocturno del hueco.” The poem is filled with her son’s poetic yet innocent questions that he would ask when he was much younger, which Goldman kept records of in a diary. “Sometimes you can incorporate voices that are not your own,” she said.

An advice that Goldman received by one of her mentors was not to fall into the cliche, and what is the expected outcome of a poem.

“When you start writing poetry, you tend to go to the common places, the rhythms, the adjectives,” she said. The mind always has connections, she added, “but [has] to break those connections when writing poetry…it means from something familiar you have to make something unfamiliar.”